PFAS Rule Information for Waterworks (webinar) - August 25, 2025 - Recording / Slides

Click here to visit the ODW PFAS Sampling Interactive Web Map Application.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of man-made chemicals that includes PFOA, PFOS, GenX, and many other chemicals. Examples of where PFAS can be found include cleaners, textiles, leather, paper and paints, fire-fighting foams, and wire insulation.

On April 10, 2024 EPA announced the final National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (see more info below) establishing legally enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for six PFAS in drinking water. Waterworks will have three years to complete initial monitoring (by 2027), followed by ongoing compliance monitoring. Waterworks will have five years (by 2029) to implement solution that reduce PFAS levels if monitoring shows that drinking water levels exceed the MCLs.

In response to this regulation, the VDH Office of Drinking Water is working closely with water utility providers to monitor the water that is provided to Virginia residents.

- EPA PFAS Rule

- FAQs

- VA PFAS Sampling

- PFAS Resources

- Financial Resources

- PFAS & Health

- Contact us

- ODW PFAS Studies

US EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulation for PFAS in Drinking Water

On April 10, 2024, EPA announced a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) establishing legally enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for six PFAS in drinking water. This includes PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA as contaminants with individual MCLs, and PFAS mixtures containing at least two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS using a Hazard Index MCL to account for the combined and co-occurring levels of these PFAS in drinking water.

Webinars from EPA introducing the PFAS Rule

- Webinar for the General Public (April 16, 2024):

- Webinar for Drinking Water Utilities and Professionals Technical Overview:

EPA has finalized health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) for these PFAS.

| Compound | Final MCLG | Final MCL (enforceable levels) |

| PFOA | Zero | 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt) (also expressed as ng/L) |

| PFOS | Zero | 4.0 ppt |

| PFHxS | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| PFNA | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| HFPO-DA (commonly known as GenX Chemicals) | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| Mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS | 1 (unitless)

Hazard Index |

1 (unitless)

Hazard Index |

The final rule requires:

- Public water systems must monitor for these PFAS and have three years to complete initial monitoring (by 2027), followed by ongoing compliance monitoring. Water systems must also provide the public with information on the levels of these PFAS in their drinking water beginning in 2027.

- Public water systems have five years (by 2029) to implement solutions that reduce these PFAS if monitoring shows that drinking water levels exceed these MCLs.

- Beginning in five years (2029), public water systems that have PFAS in drinking water which violates one or more of these MCLs must take action to reduce levels of these PFAS in their drinking water and must provide notification to the public of the violation.

Additional supporting materials, including a frequently asked questions document and several facts sheets, are available on EPA’s website: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

On April 26, 2024, EPA’s PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (the PFAS Rule) was published in the Federal Register. The PFAS Rule established legally enforceable levels for six PFAS known to occur individually and/or as mixtures in drinking water. Under the PFAS Rule, EPA will regulate five PFAS chemicals as individual compounds. They are PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, and HFPO-DA. EPA will also regulate four PFAS chemicals as a mixture: PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS.

PFAS can often be found together and in varying combinations as mixtures. Decades of research show mixtures of different chemicals can have additive health effects, even if the individual chemicals are each present at lower levels. With this rule, EPA has set limits for these chemicals individually and/or as mixtures.

On May 14, 2025, EPA announced that it will keep the current regulations for PFOA and PFOS. EPA also announced that it intends to rescind the regulations for PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA (Gen-X), and the Hazard Index, and reconsider the regulatory determinations that led to these regulations. EPA intends to issue a proposed rule in late 2025 and finalize that rule in the spring of 2026.

| PFAS Compound | MCL (1) |

| Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | 4.0 ppt(2) |

| Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) | 4.0 ppt |

| Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) | 10 ppt |

| Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | 10 ppt |

| Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO–DA) | 10 ppt |

| A Hazard Index (HI) MCL to account for dose-additive health effects for mixtures that could include two or more of four PFAS (PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO–DA, and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS)). | HI = 1 (3) |

| NOTES: | |

| (1) The MCL (Maximum Contaminant Level) is the highest level of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water. | |

| (2) ppt = parts per trillion | |

| (3) The Hazard Index (HI) is a number that is calculated based on the contaminants present and their concentrations. | |

- Well

- Rainwater Cistern

- Spring

- Pond

- Hauled Water

- Affect growth, learning, and behavior of infants and children;

- Lower a woman’s chance of getting pregnant;

- Interfere with the body’s natural hormones;

- Increase cholesterol levels;

- Affect the immune system; or

- Increase the risk of certain cancers.

- If you remain concerned about the level of PFAS in your drinking water:

- Contact your state environmental protection agency or health department and your local water utility to find out what actions they recommend.

- If possible, consider using an alternate water source for drinking, preparing food, cooking, brushing teeth, preparing baby formula, and any other activity when your family might swallow water.

- Consider installing in-home water treatment (e.g., filters) that is certified to lower the levels of PFAS in your water. Go to EPA Home Water Filters Factsheet for more information.

The Workgroup is in the process of designing a PFAS Sampling & Monitoring study in Virginia drinking water. Per HB586, no more than 50 waterworks and/or water sources will be covered under this sampling event. Selection of such waterworks and water sources will be based on two major criteria i.e. protecting public health, and maximum risk reduction.

Sample Training Webinar slides from April 14, 2021: Sampling for PFAS & What to Expect after Sampling

Below is the VA PFAS Sampling Training Video.

PFAS Resources by Type

- EPA Guideline on PFAS Rule Implementation

- US. EPA Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances webpage

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Your Health webpage

- Department of Development Environment, Safety and Occupational Health Network and Information Exchange Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) webpage

- US. Food and Drug Administration information on PFAS in food and food packaging

-

- Association of State Drinking Water Administrators Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) State Drinking Water Program Challenges webpage

- PFAS/LCRI Implementation Cost Study

- Interstate Technology Regulatory Council (ITRC) PFAS — Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances webpage

- Association of State Drinking Water Administrators

- National Groundwater Association Groundwater and PFAS webpage

- National Academy of Sciences

- VA PFAS Sample Study Summary

- PFAS Reporting FAQ

- DCLS Certified PFAS Laboratories 12-1-25

PFAS may enter a person’s body when they drink water or eat food that has been contaminated with PFAS. Unborn babies may be exposed to PFAS if their mother ingests PFAS while she is pregnant, and babies may be exposed through breastmilk. Inhalation of PFAS contaminated water can be a source of industrial exposures for employees (see the Business and Employee Exposure section below). PFAS are also present in many consumer products. Studies in humans and animals show that there may be negative health effects from exposure to certain PFAS. Completely stopping exposure to PFAS is not practical, because they are so common and present throughout the world.

- Affect growth, learning, and behavior of infants and children;

- Lower a woman’s chance of getting pregnant;

- Interfere with the body’s natural hormones;

- Increase cholesterol levels;

- Affect the immune system; or

- Increase the risk of certain cancers.

- Nonstick cookware, like pots and pans

- Furniture and carpet that is stain-resistant

- Clothing treated with water, stain, or dirt repellant

- Non-stick food packaging, like French fry cartons, microwave popcorn bags, and pizza boxes

- Makeup and other personal care products that have ingredients with “fluoro” or “perfluoro” in the name

- Tell you where or how you were exposed to PFAS found in your body;

- Tell you what, if any, health problems might occur or have occurred because of PFAS in your body; or

- Be used by your doctor to guide treatment decisions.

- Most people in the U.S. have measurable amounts of PFAS in their body because PFAS are commonly used in commercial and industrial products.

- The PFAS blood test is not a clinical test and cannot tell you whether your health has been or will be affected.

- Many health issues associated with PFAS, such as increased cholesterol and decreased thyroid hormone levels, commonly occur in the population as a whole – even when not associated with high levels of PFAS in the blood.

- These health issues can be caused by many factors, and there is no way to know or predict if PFAS exposure has or will cause your health problem.

- If you have specific health concerns, please consult your doctor for the best treatment choices for you.

- It is complicated to get a PFAS blood test.

- It is not a routine clinical test, so you would need to contact a private lab directly to arrange the test and it is unlikely that insurance would cover the cost.

- There are hundreds of PFAS around us. Labs can only test for a small number of PFAS in blood.

- Vista Analytical Laboratory; 916-673-1520,vista-analytical.com

- Quest Diagnostics; 1-866-697-8378;questdiagnostics.com

- SGS AXYS; 1-888-373-0881;sgsaxys.com

- At the point of entry (POE) where treatment all of the water entering the household plumbing system occurs, or;

- At the point of use (POU) which is often at the kitchen sink or primary source of water for drinking or cooking (potentially also including a water line to the refrigerator if it has a plumbed in water line).

Robert Edelman, PE

Director, Division of Technical Services

Phone: (804) 864-7490

Email: Robert.Edelman@vdh.virginia.gov

Bailey Davis

Phase 1 Sample Study Summary

The Virginia Department of Health Office of Drinking Water (ODW), in conjunction with the Virginia Per and Poly Fluoroalkyl Substances (VA PFAS) work group, designed the sample study to prioritize sites for measuring Per and Poly Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) concentrations in drinking water and major sources of water and generate statewide occurrence data, subject to the limitations in 2020 Acts of Assembly Chapter 611 (HB586). The 2020 Acts of Assembly Chapter 611 states that in determining the current levels of PFAS contamination in public drinking water, “the Department of Health shall sample no more than 50 representative waterworks and major sources of water...”

Phase 1 sampling used a hybrid sampling approach, considering the following information:

- Waterworks size and population served;

- Known locations of potential PFAS contamination

- Military or commercial airports (from U.S. Geological Survey data);

- Unlined landfills;

- Virginia Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) discharge locations;

- Discharge points for publicly owned treatment works (POTWs); and

- Major river networks in Virginia.

ODW selected the 17 largest waterworks in the state, which serve approximately 4.5 million consumers. This group represents 23 raw water sources, 21 water treatment plants, and 12 consecutive connections. ODW selected to monitor drinking water at the entry points to the distribution system, at the water treatment plants, and at consecutive connections at these 17 waterworks. All these samples represent “finished water,” which means the drinking water has gone through the treatment process before going into the waterworks’ distribution system, i.e., the “entry point.”

Based on the compilation of potential sources of PFAS contamination, ODW and the PFAS work group selected 11 waterworks that use groundwater as their water source and have a well or wells to withdraw groundwater within 1 mile of potential sources of PFAS contamination.

ODW also identified major surface water supplies for sampling based on potential sources of PFAS contamination that DEQ identified from SIC codes and information in VPDES permits. This identified 45 drinking water intakes potentially impacted by the discharges. ODW prioritized these 45 intakes and selected 22 major sources of water for sampling. ODW sampled surface water intakes or untreated source water as directed by HB586. Overall, a total of 45 waterworks were sampled in Phase 1.

Phase 2 Sample Study Summary

As follow-up to the PFAS monitoring and occurrence study undertaken in 2021, VDH, through the Office of Drinking Water (ODW) completed a Phase 2 PFAS Sampling Program with samples collected in July 2022, through December 2023, with some follow-up samples collected in early 2024. The purpose of this sampling program was to collect additional data on the occurrence of PFAS in Virginia public drinking water supplies, to assess impact on Virginia waterworks, and to help Virginia waterworks prepare to address PFAS.

Phase 2 sampling used a hybrid sampling approach, sampling at entry points selected with these guidelines:

- Surface water sources at community waterworks

- GUDI sources at community waterworks

- Groundwater sources at potential risk from PFAS contamination

- Groundwater sources at selected small community waterworks (prioritizing those serving less than 500 persons)

- Spread sampling across the counties in the state, to the extent possible

- Subject to budget and resource limitations

During 2023, VDH-ODW staff conducted sampling for PFAS at the entry point to the distribution systems. VDH-ODW staff reached out to the selected waterworks to schedule the sampling. VDH contracted with an external laboratory to perform all analyses for the study. The laboratory returned results to VDH following analysis. Following quality assurance/quality control review of the laboratory reports, VDH-ODW shared the reports with waterworks. Waterworks had no expenses for this sampling.

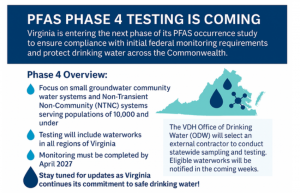

Phase 3 Sample Study Summary

Following up on the Phase 1 and Phase 2 PFAS monitoring and occurrence studies, VDH ODW completed a Phase 3 PFAS Sampling Program with samples collected in September 2024 through April 2025. The purpose of this sampling program was to collect additional data on the occurrence of PFAS in Virginia public drinking water supplies, to assess impact on Virginia waterworks, and to help Virginia waterworks prepare to address PFAS.

Phase 3 sampling used a hybrid sampling approach, sampling at entry points selected with these guidelines:

- Groundwater sources at selected small community waterworks (prioritizing those serving less than 500 persons)

- NTNC and community waterworks with groundwater sources at potential risk from PFAS contamination

- Not already sampled by VDH ODW

- Not covered by Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 5 (UCMR5) sampling

- Spread across the counties in the state, to the extent possible

- Subject to budget and resource limitations

During 2024 and 2025, VDH-ODW staff conducted sampling for PFAS at the entry point to the distribution systems. VDH-ODW staff reached out to the selected waterworks to schedule the sampling. VDH contracted with an external laboratory to perform all analyses for the study. The laboratory returned results to VDH following analysis. Following quality assurance/quality control review of the laboratory reports, VDH-ODW shared the reports with waterworks. Waterworks had no expenses for this sampling.

PFAS Sample Results Summary

VDH-ODW has compiled and reviewed the sampling results and performed appropriate quality assurance/quality control procedures. The sample results from 2021 through 2025 are summarized on the PFAS web page in the ODW PFAS Dashboard. The Dashboard consists of a web map with clickable icons representing the sample locations. VDH provided technical assistance as requested throughout this process to the waterworks.

The following table provides a summary of the PFAS monitoring and occurrence study phases completed. The table contains counts of waterworks (water systems or systems) with sample results above the levels stated in the PFAS Rule (second column from left).

To address the PFAS above EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs), waterworks will generally need to conduct additional sampling and identify actions, to bring the waterworks into compliance with the PFAS MCLs. Actions may include, but are not limited to, shutting down the source, replacing the source, blending with another source to bring the PFAS levels below the MCLs, or installing treatment.

PFAS Sample Summary

| Analyte | Criteria parts per trillion (ppt) |

Phase 1 2021 | Phase 2.1 2022 | Phase 2.2 2023 | Phase 3 2024-2025 | Total** |

| PFOA | (above 4.0) | 4 systems | None | 5 systems | 22 systems | 30 systems |

| PFOS | (above 4.0) | 5 systems | 3 systems | 9 systems | 13 systems | 25 systems |

| GenX | (above 10)* | 1 system | 1 system | None | None | 1 system |

| PFBS | (above 2000)* | None | None | None | None | None |

| PFNA | (above 10)* | None | None | None | None | None |

| PFHxS | (above 10)* | None | None | 1 system | 3 systems | 4 systems |

| Hazard Index (above 1; see above*) | None | None | 1 system | 1 system | 2 systems | |

| Waterworks to Address PFAS | 7 | 4 | 9 | 26 | 58 | |

| Waterworks Sampled | 45 | 48 | 221 | 228 | 476 | |

| Population Served | 5,226,000 | 557,000 | 3,934,000 | 71,680 | 5,984,944 | |

** Total includes some systems that were sampled in both Phase 1 and Phase 2; these systems were counted once in the total

If you have questions about the Phase 2 PFAS sampling program, please contact:

| Robert Edelman, PE

Director of Technical Services, 804-864-7490 |

Phase 4 Coming Soon